At the beginning of the 1981, two American corporations welcomed new leaders: Coca-Cola appointed Roberto Goizueta, and General Electric appointed Jack Welch. Both served at the helm of their respective companies for nearly 20 years and retired with great honor. While both Coca-Cola and General Electric were celebrated as iconic American enterprises, their businesses were vastly different—one sold sweetened soda, and the other cutting-edge turbines. However, the dollars that investors put into these companies in the 1980s were no different. Nearly half a century later, the fortunes of these two companies have diverged greatly, as have the returns to their shareholders.

What made the difference? I’m planning to complete a series analyzing the companies under the leadership of Goizueta and Welch and investigating the reasons behind their divergent paths. To start, I want to turn back the clock to when these two great entrepreneurs first took over.

At the beginning of 1981, Coca-Cola’s former Chairman and CEO, J. Paul Austin, retired after leading the company for almost 20 years. Alongside the newly appointed Chairman, Roberto Goizueta, Donald Keough also took his new role as President and Chief Operating Officer. What did they inherit?

We can get a glimpse of Coca-Cola's situation at the time from the first annual report (for the 1980 fiscal year) released after Roberto Goizueta took office.

The World Coca-Cola was in

But before diving into the annual report, let’s first revisit the historical context of the time: no company operates in isolation from the macro environment, especially during the extraordinary 1970s.

The roots of the 1970s upheavals can be traced back another decade. In the 1960s, against the backdrop of post-war economic recovery and under the initiatives of John F. Kennedy’s "New Frontier" and Lyndon B. Johnson’s "Great Society" programs, Americans enjoyed a period of economic prosperity driven by low tax rates and high government spending. During his six-year presidency, Johnson waged two wars: the War on Poverty and the war in Vietnam. The former spent billions of dollars on social security, Medicare, education, and transportation, while the latter sent over 2.7 million American soldiers to Southeast Asia over nearly a decade1. Throughout this period, the Federal Reserve maintained low short-term interest rates, enabling the government to borrow cheaply to finance these wars. Although the post-World War II economic boom under the Bretton Woods system encountered some turbulence in the 1960s, it never fully dissipated.

However, prosperities always end, and bills always come due. The low interest rates fueled demand for consumer goods and labor, leading to rising inflation by the late 1960s. In January 1970, newly appointed Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns faced an inflation rate approaching 6%, the highest in 20 years, while unemployment steadily climbed to 6.1% by 1971.

Under immense pressure, on August 15, 1971, President Nixon announced the unilateral suspension of the dollar’s convertibility into gold, marking the shift from the fixed exchange rate system of Bretton Woods to a floating exchange rate system, causing the dollar to depreciate relative to gold and other currencies. This move was just one part of the Nixon Shock, which also included wage and price controls and increased tariffs.

The dollar’s depreciation was one of the triggers for the first oil crisis in 1973. In October 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) announced an oil embargo against countries that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War, leading to the first oil crisis. The embargo lasted until March 1974, driving oil prices from $3 per barrel to $12 per barrel.

The first oil crisis, the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, Nixon’s economic policies, and the deficits caused by the Vietnam War collectively triggered the 1973-1975 recession, marking the end of post-war economic prosperity in Western countries2.

Although the economy began to recover when Jimmy Carter took office in 1977, high inflation persisted, rising from 5.8% in 1976 to 7.7% in 1978. Many blamed this on the loose monetary policies and cheap credit of the 1970s. History would prove that this bout of high inflation was not easily resolved. In 1979, the Islamic Revolution in Iran and the subsequent Iran-Iraq War triggered the second oil crisis, further exacerbating inflation, which soared to double digits: 11.3% in 1979 and 13.5% in 1980. In mid-1979, Carter appointed Paul Volcker, arguably the greatest Federal Reserve Chairman in history. Volcker’s tight monetary policies led to an unemployment rate as high as 7.8%, which may have contributed to Reagan’s victory in the 1980 presidential election.

Coca-Cola in 1970s

Had we stood in Atlanta in 1969 on the threshold of seventies, and were endowed with some Gypsy ability to see into the future, I think that we would have quailed at the prospect that lay before us.

- A Coca-Cola executive in 19793

After drifting somewhat in the 1970s…

- 1989 Chairman's Letter, Berkshire Hathaway Inc.

The 1970s were not the best of times for Coca-Cola either. The company faced fierce competition from Pepsi, investigations into poor working conditions for undocumented immigrants, criticism from environmentalists over its “one-way” containers, continuous charges from the Federal Trade Commission, constraints from bottlers with permanent contracts, and the impact of volatile international politics.

Despite the volatile conditions, Coca-Cola continued to grow steadily throughout the 1970s. Under J. Paul Austin's leadership, the company's sales increased from $567 million and profits of $47 million in 1962 to $5.9 billion in sales and $422 million in profits by 1980—nearly a tenfold increase, with a compound annual growth rate of approximately 13%, though a substantial portion of this growth was fueled by high inflation4.

With his early career rooted in overseas markets, Austin prioritized Coca-Cola's international expansion, successfully taking the brand global and further solidifying its status as a symbol of American culture. The food division he established in 1967, anchored by Minute Maid, had already reached $500 million in sales. Additionally, The Wine Spectrum, the wine business he built through acquisitions, was selling over 3 million cases of wine annually and growing at an impressive 40% per year.

Austin’s achievements were significant, though profit growth in his final year at Coca-Cola was underwhelming.

Coca-Cola, as presented in 1980’s 10-K

In 1980, Coca-Cola's sales increased by an impressive 19% to $5.9 billion, while operating profits increased by a more modest 7%, reaching $768 million. The company's net income ($422 million) and earnings per share ($3.42) were constrained by significantly higher interest rates and taxes, resulting in a slight growth of just 0.5% compared to the previous year. Looking back at the 1970s, Coca-Cola achieved a compound annual growth rate of around 12% in both sales and profits. However, this year, profit growth lagged notably behind revenue, likely due to the impact of double-digit inflation, despite the company's price adjustments in 1980.

Nevertheless, shareholders had reason to celebrate. In 1980, Coca-Cola increased its dividend per share by 10.2%: the board of directors raised the quarterly dividend from 54 cents to 58 cents, bringing the annual dividend to $2.32, a 7.5% increase from the previous year, with a payout ratio of 67%. This marked the 19th consecutive year that the company had raised its dividend.

The company's primary market, profit source, and assets were in the United States. Coca-Cola employed about 19,500 people domestically and 21,500 people internationally.

“Management Identifies Long-Range Goals”

In his first letter to shareholders, Goizueta clearly laid out his long-term goals:

In recognition of higher rates of inflation, the Company’s goals during the decade of the 1980s will be to achieve unit growth rates greater than those of the markets in which we do business, earnings growth above historical trends and significantly higher than the rate of inflation, and increased returns on assets.

While Coca-Cola's past annual reports frequently highlighted returns on equity exceeding 20%, this was the first time the company explicitly incorporated return on capital into its long-term objectives. For example, in the 1979 letter to shareholders, J. Paul Austin had focused more on the company’s growth and expansion. After conducting intensive interviews with Coca-Cola’s executives, Goizueta noted that many were "simply reacting to competition when setting their goals—some aimed at increasing sales, others at market share, while only a few were concerned with return on capital.5" Goizueta, however, recognized that an excessive focus on market share could jeopardize the company’s financial sustainability. In his carefully crafted Strategies for the 1980s, Goizueta stressed that "the growth in profits of our highly successful existing main businesses, and those we may choose to enter, must significantly outpace inflation, thereby providing our shareholders with an above-average total return on their investment."

Goizueta also highlighted that the company would take efficiency more seriously.

With these goals in mind, we conducted an intensive global review of operating expense budgets during 1980 to reinsure that our operations are being run as efficiently as possible. We also are reexamining the way we manage our working capital requirements to provide added funds for investment in the various areas of our business. Furthermore, we will be looking closer than ever before at the management of productivities—of assets and of people.

Capital Structure and Working Capital

In 1980, Coca-Cola Company’s total assets stood at $3.41 billion, with liabilities amounting to $1.33 billion, resulting in a debt ratio of 39%. The company held $130 million in cash, $100 million in short-term securities, $523 million in accounts receivable, and $810 million in inventory. Its property, plant, and equipment totaled approximately $2.1 billion, with $1.1 billion invested in machinery and equipment.

The company’s primary current liabilities included $733 million in accounts payable and accrued expenses, as well as $233 million in accrued taxes.

Coca-Cola had $133 million in long-term debt, including a new issuance in 1980 of $100 million in five-year notes at an "attractive" interest rate of 9.875%. Management noted that “the sharp decline in interest rates provided an opportunity to substitute intermediate-term debt for some of the company’s short-term, primarily seasonal, borrowings.” Additionally, the company held several smaller long-term debts, with maturities extending as far as 2010 and interest rates ranging from 5% to 15.8%. Management emphasized that long-term interest-bearing debt to shareholders' equity was only 6%.

The company’s $433 million in profits, combined with $134 million in depreciation and other adjustments, generated a working capital inflow of $627 million. Including $100 million from financing activities, $77.05 million from the disposal of fixed assets, and other items, the total working capital inflow reached $804 million. Meanwhile, working capital outflows included $267 million in dividends to shareholders, $287 million in new fixed assets, and various other investments, totaling $665 million. This resulted in a net increase in working capital of $139 million. Breaking this down further, the company’s cash increased by $22.8 million, short-term securities investments rose by $60 million, accounts receivable grew by $88.04 million (+20.0%), inventory expanded by $140 million (+20.9%), and accounts payable and accrued expenses increased by $156 million (+27.1%).

The higher working capital, particularly the significant increases in inventory and accounts receivable, was partly driven by inflation, which raised both procurement costs and sales prices. They were partially offset by the larger increase in accounts payable, reflecting the company’s “maximum use of suppliers’ credit” and strong bargaining position.

In an inflationary environment, the accounting method for inventory becomes crucial. The company used the Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) accounting method for most of its inventories. Compared to the First-In-First-Out (FIFO) or average cost methods, LIFO could understate both profits and inventory values. If the latest costs were used, the value of the company’s inventory in 1980 would have increased by an additional $109 million (13% of the $810 million in inventory reported).

At the same time, the cost of newly acquired fixed assets far exceeded depreciation expenses—almost doubling them. Inflation likely had had a more significant impact on the increasing capital expenditures than business expansion did. Even if Coca-Cola only intended to maintain its existing scale of operations, the cost of acquiring fixed assets would be substantially higher than that year’s depreciation. In fact, according to the inflation-adjusted supplemental data disclosed under FASB Statement No. 33, if adjusted for current prices, depreciation and amortization expenses would rise from $136 million to $226 million—much closer to the $287 million actually invested in fixed assets that year.

Fortunately, Coca-Cola’s strong cash flow was sufficient to support the company’s rapid growth while paying substantial dividends to shareholders. The company’s market position and product characteristics also allowed it to pass on price increases to customers—though it’s important to note that such adjustments typically come with a lag. No company truly benefits from the economic instability brought on by high inflation.

Soft-drink Division

Soft drinks have always been Coca-Cola’s cornerstone, and 1980 was no exception, contributing 76% of sales and 85% of gross profit. In 1980, the company sold approximately 135 billion servings of 8-ounce soft drinks (measured as finished products). Product sales increased by 20%, while sales profit grew by 7%. The growth in sales was primarily driven by price adjustments: in the U.S., unit sales at retail were by 4%, while actual syrup shipments only saw a 2% increase. The smaller growth in syrup sales was partly due to bottlers and wholesalers stockpiling in December 1979 ahead of the January 1980 price increase. The company anticipated that increased per capita consumption of soft drinks and expanded distribution channels would provide a favorable environment for volume growth. Despite a slightly weak economy, Coca-Cola still expected industry growth to be 3% in 1981, with the ambition outpacing the industry average:

"By commitment to high quality, continued product improvement, innovative packaging, and sales support to its bottlers and wholesalers, Coca-Cola is positioned to gain a larger share of the U.S. market.

In July 1980, President Carter signed the Soft Drink Interbrand Competition Act, which affirmed the legality of U.S. soft drink manufacturers' territorial restrictions on bottlers. Coca-Cola believed that the act strengthened its bottling system. However, some argued that Coca-Cola might not have actually wanted to win the case: if the territorial contracts had been deemed illegal, Coca-Cola would have had ample reason to terminate them, freeing itself from the permanent contracts signed with bottlers long ago.

The company also approved the use of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS-55) by its bottlers. At that time, HFCS was about 20% cheaper than cane sugar thanks to the protective tariffs. Although Coca-Cola didn’t seem to directly benefit, it would undoubtedly find a way to share in the savings.6

In international markets, the company’s soft drink sales volume grew by 4%. Compared to the double-digit growth of over 10% in 1978 and 1979, the slowdown was mainly due to a series of weather, economic, and political factors. The Pacific region underperformed, failing to meet the company’s expectations as expressed in the 1979 annual report, primarily due to a rainy summer, and economic and political turmoil. In South Korea, sales declined by 10%, though the overall soft drink market in Korea performed even worse, possibly influenced by the events of May that year. In Latin America, unit sales grew by 8%, with good profit growth as well. In Europe and Africa, unit sales grew by 7%, with profits following suit.

Notably, in 1980, the company broke ground on a bottling plant in Beijing, positioning itself to enter a vast emerging market. Additionally, the company began selling Fanta in the Soviet Union in 1979 (while Pepsi held a monopoly on cola products). However, the boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics meant that Coca-Cola’s investment in the event largely went to waste.

Overall, management believed that the company had a solid foundation for both domestic and global growth and remained committed to long-term development.

Food Division

The food division was built on Minute Maid, who was acquired by Coca-Cola in 1960. The acquisition also brought Tenco, a tea and coffee company, into the fold. In 1980, the food division further expanded by incorporating Presto Products, a plastics company (formerly a public company, fully acquired by Coca-Cola in 1978), and Belmont Springs Water (acquired in 1969).

The Houston-based food division maintained a compound annual growth rate of approximately 20% over the past six years, with sales revenue reaching $1.2 billion in 1980. The division’s main products were citrus juices, which contributed 45% of total revenue in 1980, followed by coffee and tea, which accounted for 30% of total revenue.

Minute Maid was the leading brand in the rapidly growing citrus juice industry. The industry grew from $700 million five years ago to $1.2 billion, with Minute Maid capturing over 20% of the market share. Minute Maid’s orange juice held a market share greater than the combined total of its competitors. The company also introduced new orange and apple juice products. The Tenco division, which focuses on tea and coffee, also performed well.

The company began exploring international markets. Overall, Coca-Cola is confident in maintaining Minute Maid’s leadership position and plans to introduce new products to drive growth. The company expects the food division to continue growing and contribute more profits to the overall business.

The Wine Spectrum

The 1970s marked the peak of diversification among large American conglomerates. Companies with strong cash flows and ample credit resources engaged in a series of mergers and acquisitions. Corporate management claimed that they could achieve significant synergies, enhance the returns of their subsidiaries, and create value for all stakeholders.

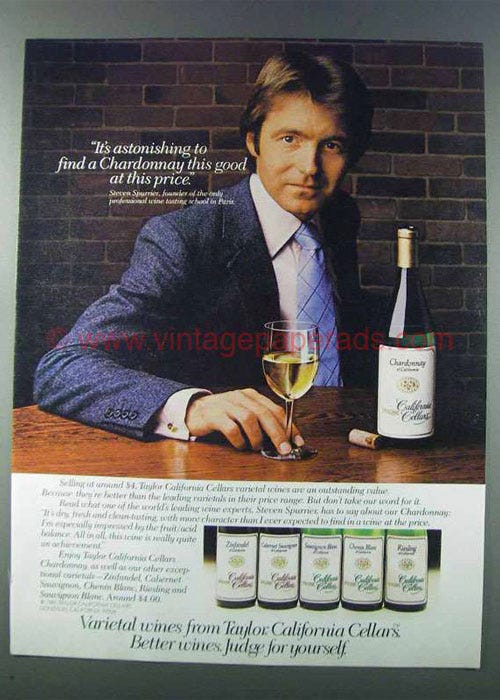

Coca-Cola's acquisition of wine companies appears to be a positive example of this trend. In 1977, Coca-Cola entered the wine industry by acquiring the 90-year-old New York-based Taylor Wine Company. Believing in the future of the American wine industry in California, Coca-Cola went on to acquire Sterling Vineyards in Napa Valley and Monterey Vineyards in Gonzales, California, in 1978.

Riding the wave of excitement generated by the 1976 Judgment of Paris—a blind tasting event where wines from California’s Napa Valley outperformed the prestigious estates of the Old World—Coca-Cola launched its "Judgement of California" advertising campaign with the tagline: "Better Wines. Judge for yourself.7" By harnessing Coca-Cola’s extensive distribution network and marketing prowess, The Wine Spectrum became the fourth-largest wine producer and distributor in the United States by 1980. Sales volume surged by nearly 40% in 1980, and revenue grew even more—a trend that had persisted for several years. Additionally, in 1980, the company began exporting California wines to the UK market.

The future of The Wine Spectrum was undoubtedly positive and exciting. The market environment also appeared optimistic: Coca-Cola’s management projected that U.S. wine consumption would grow at a compound annual growth rate of 8% over the next decade. The company hope the healthy volume and profit growth of the division could continue8.

Aqua-Chem Inc.

It is said that Austin's concern for environmental issues led to the company's investment in Aqua-Chem Inc.9, a company primarily engaged in the production and sale of boilers and water purification systems. In 1970, Coca-Cola acquired Aqua-Chem, which was also listed on the New York Stock Exchange at the time, by issuing 1.754 million shares of stock. Based on Coca-Cola’s stock price then, the acquisition was valued at approximately $150 million. Aqua-Chem's revenue at the time was $55 million, with a net profit of $2.6 million, reflecting in a high acquisition price-to-earnings ratio of 57 times10.

In 1980, Aqua-Chem, headquartered in Milwaukee, reported $130 million in revenue and a corresponding increase in profits. Both its water treatment equipment and Cleaver-Brooks boiler divisions experienced solid growth.

Looking Ahead from 1980

In 1980, Coca-Cola had a solid balance sheet and a healthy income statement. From a financial perspective, the company was undoubtedly in good shape. If this level of profitability could be sustained, Coca-Cola could be "a good investment at a fair price."

But could Coca-Cola maintain its profitability? Comparing to manufacturing jet engines, gas turbines, chips, or cars, making sweetened drinks is not cutting-edge science. It doesn’t require renowned professors, PhDs, or engineers to bring the latest technology, nor does it demand massive capital investment to get started. However, not anyone can be like Coca-Cola. As Warren Buffett said in his 1998 speech at the University of Florida, "Give me $10 billion dollars and how much can I hurt Coca-Cola around the world? I can’t do it."

Yet, Buffett's words might have understated the challenges Coca-Cola faced. Looking back from 2024 to 1980, “of course” Coca-Cola could continue to thrive for another 50 years. However, during the 1970s and 1980s, Coca-Cola was not only confronting severe scrutiny from the media, social groups, and government agencies—with agendas on health, environmental concerns, antitrust matters, and more—but also facing aggressive competition from rivals like Pepsi. While the global soft drink market was unlikely to undergo a radical transformation overnight, Coca-Cola's dominance was not unassailable.

In 1980, investors had reason to be optimistic about Coca-Cola’s new ventures. The wine business, in particular, seemed to be a successful example of synergy. In just three years, Coca-Cola had built the fourth-largest wine company in the United States. If the company continued to develop this sector, it could establish a significant business pillar beyond soft drinks. With Coca-Cola’s unmatched marketing and distribution capabilities, what other successes might the company achieve?

Coca-Cola also had a strong history of steadily increasing dividends over many years. However, in 1980, profit growth was modest, and the dividend increase was made possible by raising the payout ratio. Could investors count on this trend of dividend growth to continue?

Standing at the beginning of the 1980s, how might one envision Coca-Cola's future? And where would Roberto Goizueta and Donald Keough take the company?

Or perhaps we can ask the same question today: Will people still be drinking Coca-Cola in 2075?

William Manchester, The Glory and the Dream, 1974

Marc Levinson, An Extraordinary Time, 2016. Many other writings on this topic.

Part IV, Section 17. Mark Pendergrast, For God, Country and Coca-Cola, 2013.

Most of the financial data and graphs are from the Company’s annual reports.

Part V, Section 18. Ibid.

Part V, Section 18. Ibid.

Tim Mckirdy, The Story of Taylor California Cellars, Coca-Cola's Forgotten Foray Into the Wine Industry, 2020. Including the advertising picture below.

The 1970s saw U.S. wine consumption grow at a CAGR of 6%, rising from 267 million gallons in 1970 to 480 million gallons in 1980. Given this growth trajectory, an 8% rate, derived from a blend of linear projections and optimism, didn’t seem far-fetched—until reality proved otherwise.

And yes, like many business projections, it was way too optimistic. The U.S. wine consumption reached 1980s high at 580 million gallon in 1986, but was only 506 million gallon in 1990. Had it compounded at an 8% CAGR as projected, consumption should have reached 600 million gallons by 1983—a milestone that was not actually achieved until 2020.

Part IV, Section 17. Mark Pendergrast, For God, Country and Coca-Cola, 2013.

Gene Smith, Coca-Cola Seeks a Desalting Unit, The New York Times, Jan. 23, 1970